In my tenure as an engineer working for early-to-mid stage startups, I’ve noticed that the first iteration of the product is usually a monolith; all of the code is written in a monorepo, and the tooling, and processes are created to support it. While this helps to ship the product quick and early, it becomes difficult to scale both in terms of software systems, and teams which write code. For example, if multiple teams are creating features then merging the code becomes a bottleneck since all the code is committed to the same repository. Additionally, all of the changes being made to the code that is shared among multiple teams needs to be backward compatible, and any breaking change needs to be communicated to the relevant teams. All of this can slow down the subsequent releases.

As the startup grows, and the multiple features become products of their own, it may be required to separate the monolith into microservices. This requires a change in how systems are designed, and deployed. For example, we’d now need to trace an API request across multiple services. While many teams moving from monoliths to microservices think of them as code that is written in separate repositories, and deployed independently, they’re actually smaller subsystems of the larger software.

This post is my opinion on how Python microservices can be created. While we’ll see libraries and tools used from the Python ecosystem, the ideas discussed in the following sections can be applied to the language of your choice. We’ll create a couple of microservices, and see how we can add logging, tracing, metrics, and profiling to them. The goal is to develop a blueprint that can be used to create microservices.

Before We Begin

We’ll look at two key parts of creating a microservice: telemetry, and profiling. Telemetry includes collecting logs, and metrics. Profiling includes analysing the CPU, memory, IO, etc. Both of these put together give us the complete picture of how the microservice is performing. We’ll use OpenTelemetry and Parca for telemetry, and profiling respectively. A detailed introduction to both of these projects is beyond the scope of this post and you’re encouraged to read the relevant documentation.

Briefly, we will use a combination of zero-code and code-based instrumentation offered by OTel. The zero-code instrumentaion is helpful as it adds instrumentation to the libraries that we are using. If we’d like to instrument our code, we’ll have to use code-based instrumentaion and add it to the source ourselves.

Finally, the setup consists of two Flask apps, and Parca Agent running on the machine; everything else runs as Docker containers. We’ll run an OTel Collector exporter to collect the metrics and logs emitted from OpenTelemetry, Jaeger to display the distributed trace, and Parca Server for continuous profiling.[1]

Getting Started

For the sake of brevity, we will only look at parts of the code that are necessary for the post and will exclude all the scaffolding. The complete code is available in the repository mentioned at the end.

Microservices

We’ll begin by looking at how the microservices work. The two microservices are called “first” and “second”. The first microservice receives an API call, sleeps for duration, and makes an API call to the second. The second receives the API call and makes an API call to the /delay endpoint of HTTPBin. We are trying to mimic a real-world scenario by adding some delay, and a slow API call.

The code for the first endpoint is given below.

1 |

|

The code for the second endpoint is given below.

1 |

|

We can test the two endpoints by running the Flask apps and then making a call to the first.

1 | curl -s -XPOST localhost:5000 | jq . |

Adding automatic instrumentation

We’ll now begin by adding zero-code instrumentation to both of these microservices. The first step is to install the packages.

1 | pip install opentelemetry-distro opentelemetry-exporter-otlp |

This installs the API, SDK, opentelemetry-bootstrap, and opentelemetry-instrument. We’ll now use opentelemetry-bootstrap to install the instrumentation libraries for the libraries that we have installed. It does so by reading the list of libraries installed, and fetching the corresponding instrumentation library, if applicable.

1 | opentelemetry-bootstrap -a install |

Finally, we’ll add two bash scripts to run the apps with OTel enabled. The script for the first service is given below and the one for the second service looks similiar.

1 |

|

We’ll then send requests to the first service using curl and observe the traces of the two services. Specifically, we’re looking for how OTel does distributed tracing.

1 | for i in `seq 1 10`; do curl -s -XPOST localhost:5000 > /dev/null; done |

One of the trace generated by the first service is the following.

1 | { |

The context contains the trace_id which is the ID that will be used to trace the request across services. It also contains span_id which represents the current unit of work and that is the request received by the service. The parent_id is null which means that this is the root span; it represents the entry of the request in the mesh of services. The attributes are key-value pairs and they show that the request was received from curl on the / endpoint, and that it returned a 200 response. More detailed information on the structure of the trace can be found in the OTel documentation.[2]

To trace the request across services, OTel propagates some contextual information.[3] This allows linking the spans in a downstream service with an upstream service. In our case, the request received by the second service will be associated with the first. This is done by setting the parent_id of one of the spans in the second service to the span_id of the first service. In essence we’re creating a hierarchy. Let’s look at an example.

Here’s a span from the first service. Notice that it’s parent_id is set to a value to inidicate that it is not a root span. The attributes indicate that a request was made to http://localhost:6000/ and that is the endpoint of the second service.

1 | { |

If we were to depict the flow of request as a tree we get the following.

1 | Root Span |

Let us now look at a span from the second service. It has the same trace_id as the one from the first, and the parent_id is the span_id of the span we saw previously. The attributes indicate that this span represents the request that was made from the first service to the second.

1 | { |

If we were to depict the flow of request as a tree we get the following.

1 | Root Span |

We’ll look at one final span in the second service, and that is the child of the span mentioned above.

1 | { |

We can see that the parent_id is the span_id of the previous span, and the attributes indicate that a call was made to HttpBin. Notice that throughout this flow the trace_id has remained the same. We can now look at the final tree to see the flow of requests. Distributed tracing backends like Jaeger provide a visual representation of this flow.

1 | Root Span |

So far we’ve sent the traces to the console which is helpful for development. We’ll now look at how we can send the traces to the OpenTelemetry Collector[4], and from there to appropriate backends.

OTel Collector

Telemetry data is received, processed, and exported via the OTel Collector. It may receive logs and export them to any vendor of your choosing, or it can receive traces and export them to Jaeger. As a result, the services can submit telemetry data to the collector, which will forward it to the relevant backends. This enables the codebase to be instrumented with merely OTel, while a combination of open-source and proprietary backends can be used to process the telemetry data.

We only need to change the command in the bash script that launches the services in order to transmit the data to the Collector. Notice that we have included OTLP as an export option for all of our telemetry data. In a similar vein, we supply the endpoints — which leads to the collector(s) — to whom the data will be transferred. While all metrics can be specified as a single collection endpoint, the example below demonstrates how to send each type of data separately, allowing the collector(s) to be scaled independently.[5]

1 |

|

We need to configure the collector(s) for it to be able to recieve, transform, and export the data. This is done through a YAML file. We specify the receivers, processors, and exporters for each type of telemetry data.[6] For the sake of this post, we’ll modify the example given in the official OTel documentation slightly and send the traces to Jaeger.

1 | receivers: |

If we look at the pipeline, at the bottom of the YAML file, which processes the traces, we’ll see that we receive them in the OTLP format, batch them[7], and send them to Jaeger. Similarly, we could export the logs to a vendor of our choosing, or to a self-hosted solution like OpenSearch.

Finally, we’ll look at adding instrumention using code to the services.

Code-based Intrumentation

When we put a service into production, we will need more than just the basic monitoring that OTel provides. For instance, we might want to monitor how much time it takes for a specific part of the code to run. We can use the OTel SDK for situations like these. When we did the bootstrap step, the OTel API and SDK were installed for us. We can check this by looking for them in the list of installed packages.

1 | pip list | grep opentelemetry | grep -E "*.-(api|sdk)" |

We’ll begin by couting the number of requests that are received by the first service. To do this, we’ll first need to obtain a MeterProvider[8]. From this we will create a Meter, and then Metric Instruments. The instruments represent the actual metric that we want to track. For example, a counter.

The common package in our repository contains code to configure a MeterProvider, obtain a counter, and to incremenet it. For the sake of brevity we will only look at the change to the endpoint of the first service.

1 | _counter = create_counter( |

We are now keeping track of how many times we call the API. If we check the numbers in the console, we will find this. The value shows how many times we used curl to make requests. It is currently at 10.

1 | { |

We can create different instruments, too. Let us now use a histogram to track the time taken by HTTPBin.

1 | _histogram = create_histogram( |

Like with the previous metric, we can see it logged to the console. The output for a hisogram is sufficiently large and has been excluded for brevity.

With this we conclude how to add telemetry, both automatic and manual, using OTel. Before we move on to profiling, I’d like to point out a few things I noticed when using the Python SDK for OTel. One, there is only the console exporter for metrics and traces. I’d assume we’d need an OTLP exporter to be able to send these to the collector. Two, the logs SDK is still under development.[9] Nonetheless, OTel is a great way to add instrumentation to the services.

Profiling

Telemetry helps us observe how our program is performing by looking at logs, metrics, and traces. Another way to observe the program is by profiling it. This helps us understand how resources like memory, IO, CPU, etc. are being used. In this section we will look at how to profile our microservices using Parca. Specifically, we will profile the CPU usage.[10]

To see our service’s CPU usage over time, we will add a new endpoint which computes Fibonacci numbers. Since this is a CPU-intensive operation, it will be captured visibly in the trace. We’ll add the following endpoint to the first microservice.

1 |

|

Notice that the returned value is generated from calling _one. This function then calls _two which eventually calls _fibo. The reason it is written this way is to have them show up in the profile.

Next we will download the Parca Agent. This is an always-on profiler which reads the stack traces of programs in both user-space and kernel-space.

1 | RUN wget -O parca-agent https://github.com/parca-dev/parca-agent/releases/download/v0.30.0/parca-agent_0.30.0_`uname -s`_`uname -m` |

We’ll also add a small script which sends random requests to the endpoint.

1 | import requests |

We’ll now run the agent and the services. The Parca Server which receives the profiles and displays them is part of the Docker compose file. The agent will run on the machine and send the profiles to the server.

1 | sudo ./parca-agent --remote-store-address="localhost:7070" --node="laptop" --http-address="0.0.0.0:7071" --remote-store-insecure |

Finally, we’ll send requests to the endpoint and wait for the profiler to generate profiling data. This will be visible on localhost:7071. To query the first microservice we will need its pid, and this can be obtained by grepping for it.

1 | ps aux | grep python | grep -E "*.(first).*" |

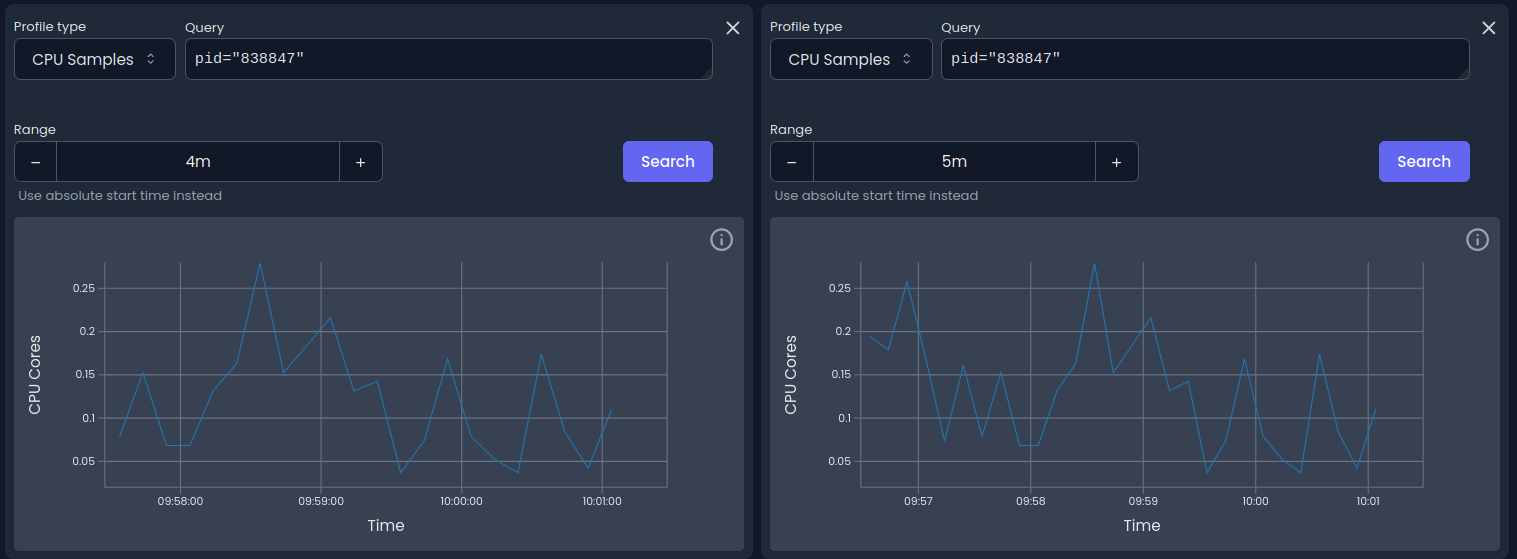

We can now query Parca and look at the profiles. The benefit of profiling is to look at how the program is performing over time. We’ll compare two profiles along side each other. Notice how we’ve used the PID to filter the profiles.

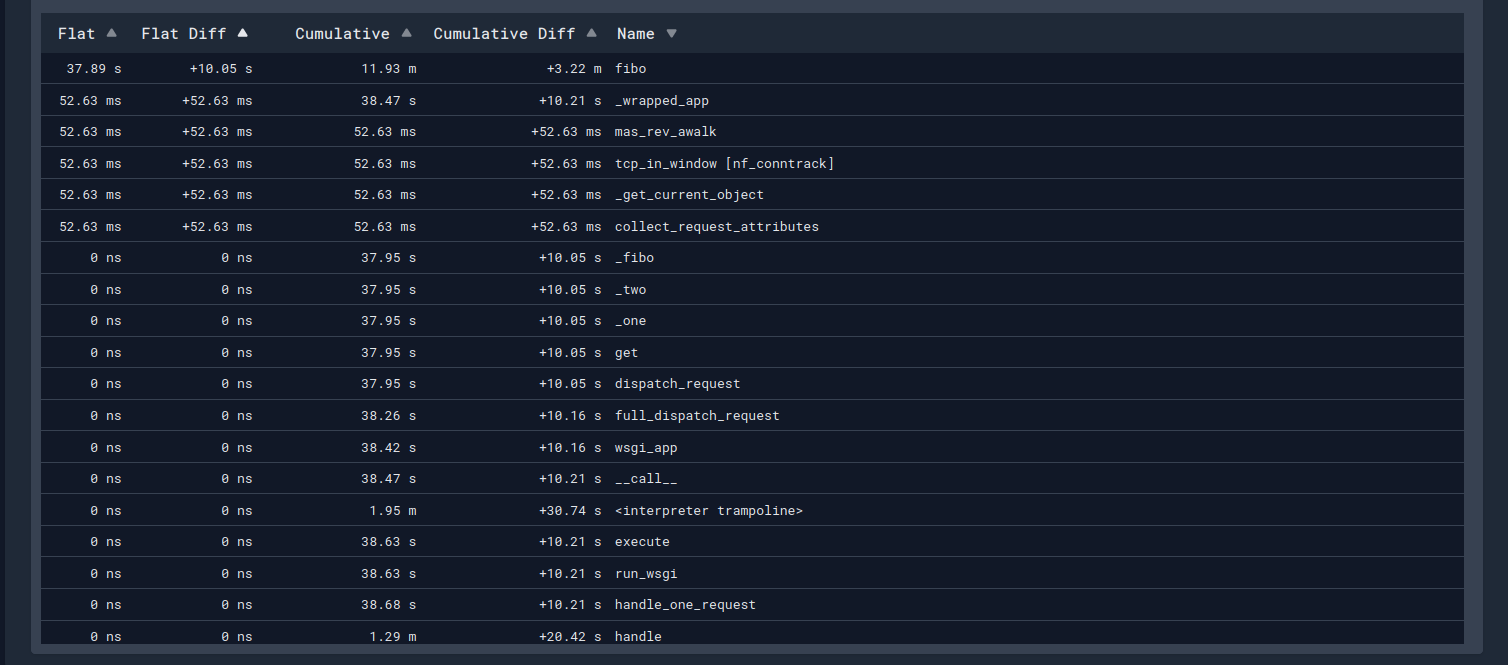

Similarly, we can look at the stack trace.

Towards the middle of the image we’ll see the call stack calling the private functions _one, _two, and _fib. In the cumulative diff column[11] we see a +10.05s. This means that between the two timeframes, the stacktrace has been running 10.05s longer; we’ve gotten slower with time. This can be confirmed by switching to the icicle graph which indicates the same.

That’s it. We’ve added profiling to our service.

Conclusion

We saw how we can add telemetry using OTel, and profiling using Parca. Both of these are great ways to observe a service in production. However, as of writing, both of these projects are in their early stages as can be seen from functionality that is yet to be developed. For example, OTel’s Python SDK is yet to add support for logging, and Parca only supports CPU profiling. Despite this, they’re both worth following as they let us add observability to our services without much effort.

This is my opinion on how to create a microservice with observability baked in. The code for this post is available on GitHub.

Footnotes and References

[1] I was unable to send traces and metrics to the collector, and from there to the appropriate backends, as I kept running into issues with gRPC. Perhaps an astute reader would like to submit a PR to fix these. :)

[2] https://opentelemetry.io/docs/concepts/signals/traces/

[3] https://opentelemetry.io/docs/concepts/context-propagation/

[4] https://opentelemetry.io/docs/collector/

[5] https://opentelemetry.io/docs/collector/scaling/

[6] https://opentelemetry.io/docs/collector/configuration/

[7] https://github.com/open-telemetry/opentelemetry-collector/blob/main/processor/batchprocessor/README.md

[8] https://opentelemetry.io/docs/concepts/signals/metrics/#meter-provider

[9] https://opentelemetry.io/docs/languages/python/instrumentation/

[10] https://www.parca.dev/docs/profiling-101/

[11] https://www.parca.dev/docs/concepts/#cumulative-and-diff-values